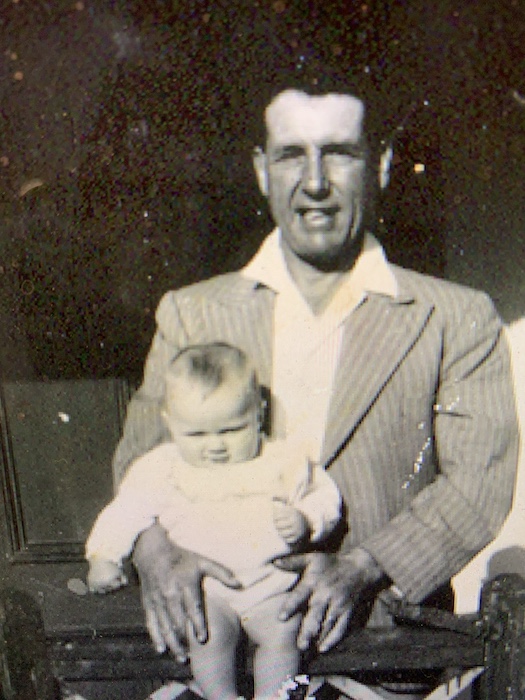

My grandfather on my Dad’s side was a great storyteller. At a time in South Africa when there was no television, our imaginations came alive and created a virtual world as we listened to stories on the radio and storytellers like my grandpa. Even though I only saw him once a year on our annual vacation trip from Johannesburg to Cape Town, I vividly recall some of the stories he told that left us spellbound and frozen in our tracks. My grandpa revelled in passing on traditional South African folk-tales, which in our case always involved stories of two animals, “Jackal & Wolf” who were constantly trying to out prank each other.

My grandfather on my Dad’s side was a great storyteller. At a time in South Africa when there was no television, our imaginations came alive and created a virtual world as we listened to stories on the radio and storytellers like my grandpa. Even though I only saw him once a year on our annual vacation trip from Johannesburg to Cape Town, I vividly recall some of the stories he told that left us spellbound and frozen in our tracks. My grandpa revelled in passing on traditional South African folk-tales, which in our case always involved stories of two animals, “Jackal & Wolf” who were constantly trying to out prank each other.

These folklore stories were bigger than life and served as a way to preserve the Dutch/Afrikaner identity. I can still picture my grandpa telling us these stories… it was like he lived inside the story creating poetry as his mind leaped from one thought to another. It was as if the exquisite beauty of the story intoxicated him as hand gestures and facial expressions swept us along to the psychological point of climax leaving us all wanting more. As I think back on this time with my grandpa, I can tell that there was this organic connection he made with us as he passed on these traditional stories from the past. He was not passing on real history but stories that made him laugh. In a way, my grandpa was sharing with us some of the ways that helped him cope with life. It was life in the apartheid era of South Africa in the late 60s in a small farmers town called Malmesbury, (60 miles from Cape Town) where my grandpa made his living as a “fitter and turner.”

These and many stories from my dad helped me to realize that I inherited a long tradition of storytelling. These stories reflected the idiom of a specific culture in a specific time and contributed to the unique identity of the Afrikaner people in South Africa. When you trace the origin of these folklore stories, researchers tell us that the bushmen (a particular pigmy tribe in southwest Africa) were the people who brought these stories to southern Africa as they passed on an oral tradition that goes all the way back to the time of the pharaohs in Egypt.

It appears that, in our family, passing on stories was a critical way to connect us with the past and to remind us of who we are in the present. I think it’s very similar to the role of oral traditions in the formation of the Bible and how stories were passed on from one generation to the next. I am specifically thinking about the creation stories in Genesis and how they came to be in our Bible. As a Hebrew student at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa, one of the first things I learned from my Hebrew professor was that Genesis 1 & 2 were written reflecting the cultural idioms of a very ancient society. At first, that freaked me out, but the prof assured me that God was not afraid to get his hands dirty as he condescended and accommodated himself to the level of people’s understanding and literary idioms of that day. We also know from the best scholarship available to us today, that parts of the Pentateuch were composed over several centuries, and that the Pentateuch (first five books of the OT) as a whole was not completed until after the Israelites returned from exile.

I am only scratching the surface on all the scholarship available to us today, but basically, scholars want you to know that 70 years in a strange land brought Israel to a national identity crisis. They no longer had the land, the temple, and the sacrifices. Everything that anchored them in their relationship with God was gone. Since all these long-standing connections were gone, the only option left to them was to bring the past into the present through an official collection of writings. All this happened ‘round about the middle of the 5thcentury BC. Peter Enns, an OT scholar, helps us to understand this better. He said,

The crisis of the exile prompted Israel to put down in writing once and for all an official declaration: “This is who we are, and this is the God we worship.” The Old Testament is not a treatise on Israel’s history for the sake of history, but a document of self-definition and spiritual encouragement: “Do not forget where we have been. Do not forget who we are—the people of God.” The creation stories are to be understood within this larger framework, as part of a larger theologically driven collection of writings that answers ancient questions of self-definition, not contemporary ones of scientific interest.*

This scholarship is eye-opening to me. It lets me know that the early chapters of Genesis are not a literal or scientific description of historical events. They are rather a theological statement written in an ancient idiom of how Israel saw itself as God’s people in the context of their surrounding Assyrian, Babylonian and Persian cultures. It was written so that grandpas and moms and dads can gather their children and tell them stories of their national identity. In response to the questions kids and teens could ask and probably did: “Dad, who are we?” “Mom, our Israelites ancestors, those guys to whom God spoke – are we still connected to them?” Moms and dads were able to tell their story from the beginning (creation) and from their “postexilic” point of view. The last book in the Jewish Bible’s is Chronicles (not Malachi), and that is not by accident. Peter Enns again makes sense as he put this fascinating textual history in perspective. He writes,

Chronicles is a postexilic rewriting of Israel’s entire history to remind the Israelites that they are still the people of God—regardless of all that has happened, and regardless of how much they have deserved every bit of misery they received. They remain God’s people, and their lineage extends to the very beginning, to Adam. The exile prompted the Israelites to write a new national history that would be meaningful to them. Rather than simply repeating the stories of the past, they rewrote them to speak to their continued existence as God’s people; they rewrote the past in order to come to terms with their present.*

That’s enough head spinning for now. Much more can be said, but I will leave it for another blog. Next time around we can gain a deeper understanding of the time Genesis was written. Especially in light of the major archaeological excavations that were performed in the library of King Ashurbanipal (668–627 BC) in the ancient city of Nineveh (the capital city of ancient Assyria). For now, these new revelations bring me to ask a few questions of us: Given our context today living in the US in the 21stcentury, what do these ancient texts say to us about being the people of God today? What stories are we telling our children? How do these ancient inspired stories help us to cope with life today?

*Peter Enns, The Evolution of Adam, Brazos Press, 2012.